Thinking with pleasure

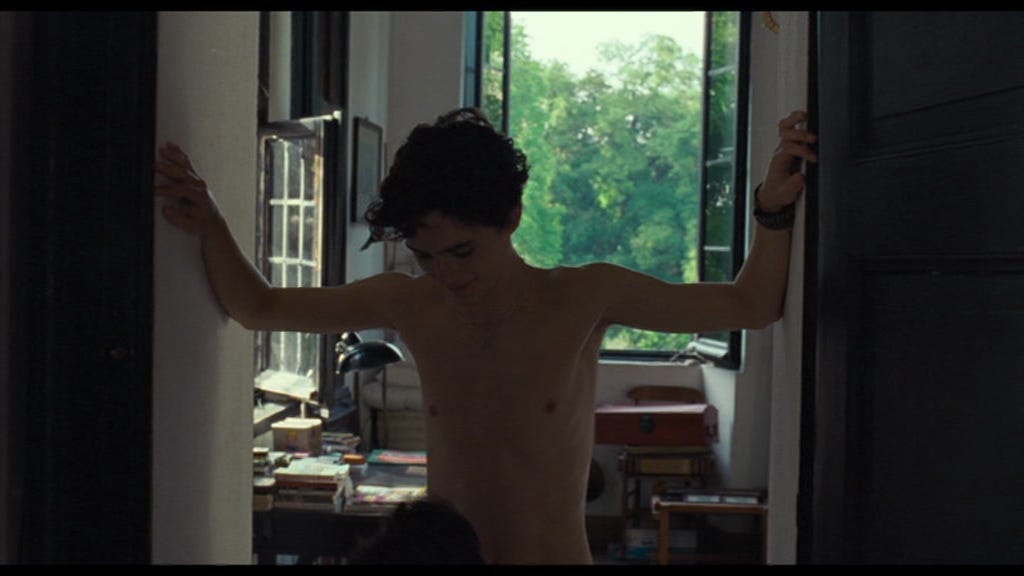

On Call Me By Your Name (Luca Guadagnino, 2017)

This post began life as a short talk I gave at the British Film Institute’s Reuben Library, to celebrate and promote THIS BOOK. I was invited by my absolutely wonderful editors, Edward Lamberti and Micheal Williams, along with two other contributors (Adam Vaughn and Claire Monk) to speak about our chapters in the book (which we hope will come out in paperback in 2026 and be a more normal price).

So, I wrote most of this chapter during lockdown, and I was writing it while I was also working on finishing my own book Quiet Pictures (out in paperback Thursday! A normal price at last! £26!), which is partly about how four women directors (Joanna Hogg, Lynne Ramsay, Lucile Hadzhlilhovic, and Celine Sciamma) use silence and the absence of dialogue as a texture and technique. So, it was a really useful counterpoint (and a lot of fun) to be working on this chapter simultaneously, which is called “Sex Sounds: On Aural Explicitness in CMBYN.”

What I focus on in the chapter are some of the strategies that CMBYN uses via sound design to indicate and emphasise sex acts that are either deliberately implied or not fully shown on screen.

So, we never see the doorway blow job, but if you listen carefully, you can hear the sound of Oliver’s mouth opening as it makes contact with flesh. The film has a highly sensuous, saturated soundscape that allows us, as attentive listeners, access to the sound of fabric against skin, the ripping of zippers, as well as sighs, moans, heavy breathing, and other instances of aural excess, something which Linda Williams remarks on in a piece that I find myself continually returning to in my own research and thinking. She writes that excess can be “marked by recourse not to the coded articulations of language but to inarticulate cries of pleasure in porn.” (‘Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, Excess’ Film Comment, 1991, 270). So that sound itself may be a form of excess.

CMBYN remains coy about full frontal male nudity, and this was something that many critics and other commentators remarked upon, and it doesn’t deploy the strategies of other non-porn films that feature explicit sex between men.

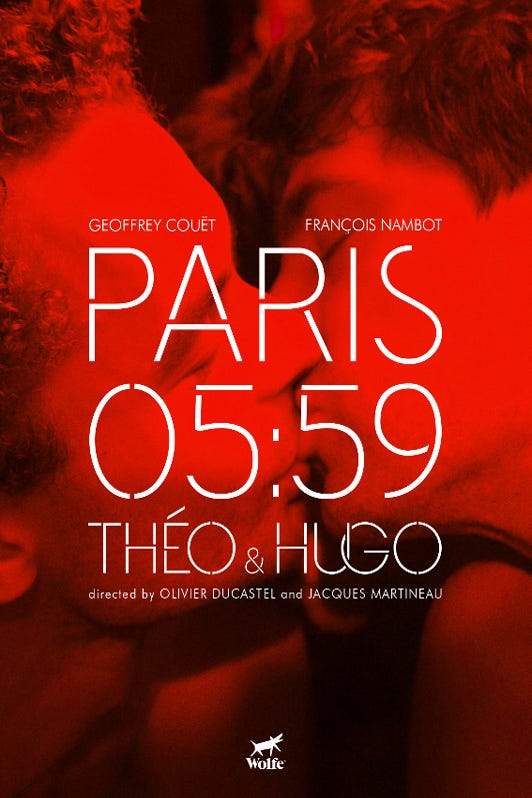

Alain Guiraudie’s 2013 l’inconnu du lac/Stranger by the Lake features both blowjobs and handjobs, but uses porn actors as body doubles for the leads—but doesn’t accord the same attention to the sound design of these acts. Here, the sex is designed to be seen, but it’s not designed to be heard in the way we can hear sex in CMBYN. Olivier Ducastel and Jacques Martineau’s queer romance Theo et Hugo from 2016 opens with an extended orgy scene in a Paris sex club, refusing to treat explicit, un-simulated sex as belonging solely to the realm of pornography, since this is where the two protagonists first meet.

CMBYN is a film that was designed for a mainstream audience in terms of what sex is allowed to occupy the visual frame. In this sense, the framing of that doorway blow job tells us everything—what would otherwise be classed as pornography is just below what we can see. The most transgressive sexual act we witness with our eyes is when Oliver almost puts his finger inside the cum-filled peach, saying “I wish everybody was as sick as you”. The peach (much like the emoji) stands in for the most forbidden image of the anal. Yet, in pornography anal play is ubiquitous across a range of potential bodies, sexualities and configurations. So, while the film looks sexually coy, it really doesn’t sound that way!

We might also consider some of what has been written about the ‘aural bottom’ of gay male pornography where “ ‘bottoms’ are typically expected to maintain an orgasmic ‘sound’ throughout intercourse. The ‘anal orgasm’, like its vaginal sister, resists easy visual identification but remains identifiable (if not authenticated) via sonic registers.” (Sharif Mowlabocus and Andy Medhust ‘six propositions on the sonics of pornography, Porn Studies, 2017: 214) I do say in the chapter that these kinds of roles are absolutely in flux, and much less hierarchical or conventionally gendered these days.

So, when Elio has his solo orgasm with the aid of the peach, we have no doubt about what is taking place just below the frame, but a solo scenario presents an interesting conundrum for this idea of the aural bottom. It’s important for the audience to know about Elio’s orgasm. We have utterances like Elio saying ‘fuck’, his heavy breathing, his damp, sweating body, and those squishing, squelchy sounds, not unlike what we have already heard earlier in the film when Oliver is enjoying his oozing soft boiled egg at breakfast. So, Guadagnino (a director who loves to tease but does not give it up) along with his production sound mixer Yves-Marie Omnes gives us orgasmic sound via Chalamet’s performance and how we imagine the sound of the ripe peach.

In the case of CMBYN we might think of its sound strategies as ‘compensating’ for the lack of visual sexual explicitness, but that the question remains unresolved for me as to whether this strategy renders the film more widely palatable or if it even acts as a form of censorship.

That said, I think we can consider the film’s sound design more generously— so that it it’s something more than evading censorship or placating less open-minded audiences. Instead, we might think of the film’s soundscape as a method for allowing the audience to, as Avgi Saketopoulou argues “think the limit with pleasure” just as Elio and Oliver are learning to think with pleasure in their explorations with music, writing, and of course through the sex they have together. As an attentive listener, we are able to experience what Vivian Sobchak claims, that “movies provoke in us ‘carnal thoughts’ that ground and inform more conscious analysis” in the sense that the things you feel in your body can be a pathway to thinking more deeply about ‘the things that matter’. Ultimately, for me, this is a film about the ambiguities of desire, and about being given permission to marinate on those desires, to follow them, to surrender to them. And it is through listening to the sex that we in turn can surrender to thinking with pleasure.

I initially misread the phrase "being given permission to marinate on those desires" along predictable lines and actually blushed