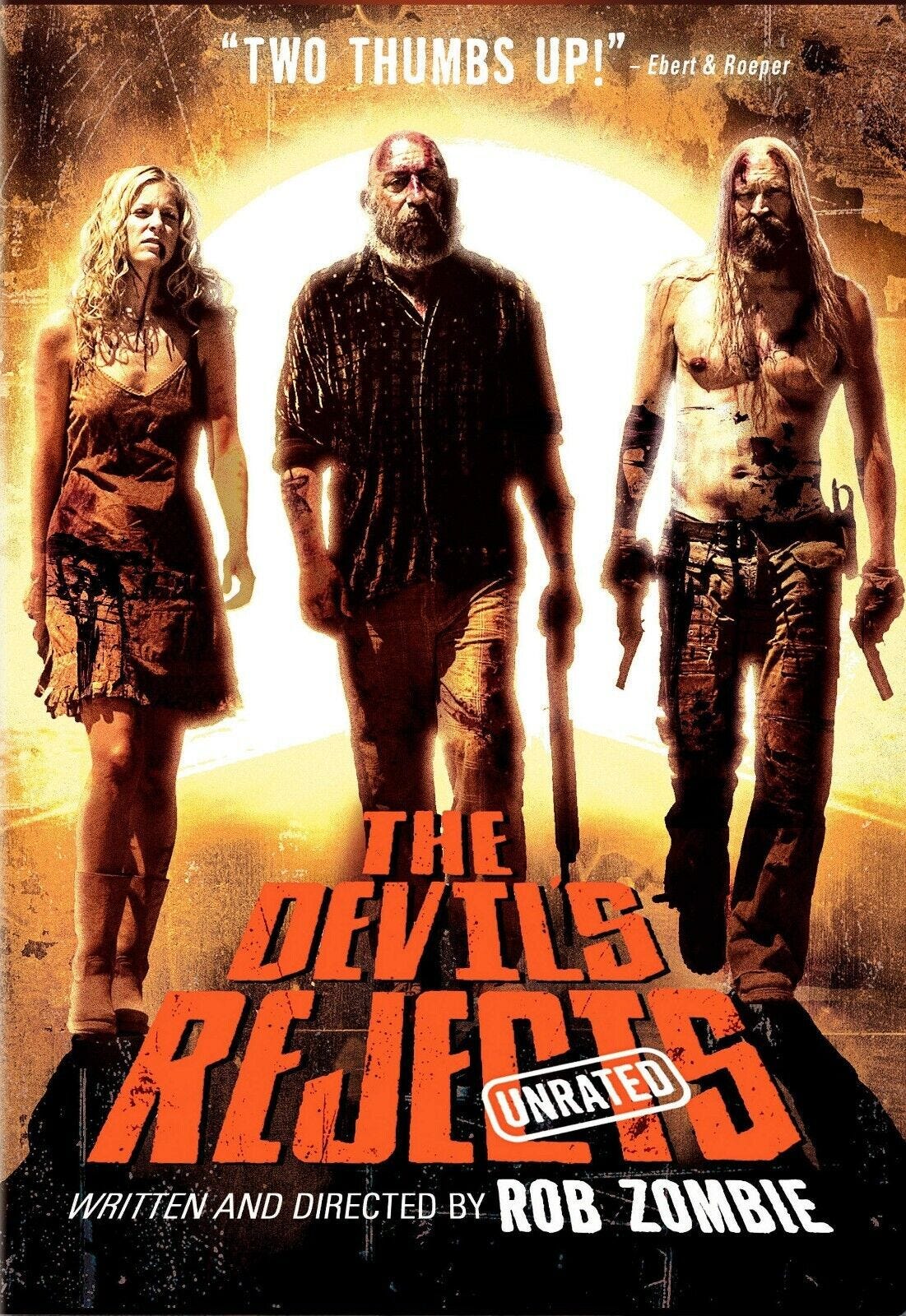

In The Devil’s Rejects, Otis (Bill Moseley) looms over Roy (Geoffrey Lewis) and declares “I am the devil and I am here to do the devil’s work.” And so it goes with my re-evaluation of the cinematic back catalogue of Rob Zombie. Since watching Lords of Salem, I have found myself more intrigued by his work. Yes, Zombie does include as many shots of Sheri Moon Zombie’s ass as one can reasonably expect (my pal dubbed these “look, my wife is hot” shots), but I must admit there is a lot more going on there than I was expecting. In Lords of Salem, I was delighted by its Trip to the Moon-inspired murals, and of course its superb soundtrack with its courageously bizarre use of The Velvet Underground’s All Tomorrow’s Parties. But what stayed with me was the substantial roles that film allows for actresses considered ‘past their prime.’ Those elder witches—they mean business, and you do not fuck with them. In a similar turn, The Devil’s Rejects features a voraciously unhinged turn from Leslie Easterbrook as Mother Firefly. Taking her cues from the ‘psychobiddy’ performances of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane and Mommie Dearest, and throwing in a dash of Sideny Lumet’s The Fugitive Kind (1960) she embodies a psychotic and unruly character and she looks like she’s having the time of her life.

The other thing that has stuck with me is the film’s soundtrack, a kind of love letter to southern rock and blues, with a finale that turns the impossibly cliched Freebird by Lynyrd Skynyrd inside out, asking us to simultaneously condemn and sympathise with Firefly band of outlaws, to somehow appreciate anew this hopelessly overplayed and covered song. When I was growing up, Freebird was still a staple of classic rock radio, and touring bands with guitarists who fancied themselves all seemed to love covering it. Freebird and its association with dive bars populated by men who would almost certainly utter Otis’ line “you’re just a city f****t in a cowboy hat” is almost a genre in itself. I hear this song, and I think about the kinds of places that you couldn’t sneak into, dusty road trips, and how I learned about parts of the American South from reading Anne Rice novels set in New Orleans.

I stumbled across this clip from The Fugitive Kind (a Tennessee Williams adaptation), a film I haven’t seen for some time, and was struck by the resonance of both the title and the idea of those who don’t belong. The Fugitive Kind could be an alternative title for The Devil’s Rejects, though it’s a different kind of Southern Gothic. The Firefly family and their compatriots are itinerant outsiders hellbent on corruption, in it for the power trip, but also because they are the kind who don’t belong and can’t belong. The Devil’s Rejects borrows the palette of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but couches its opening credit sequence in the outlaw atmosphere of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, with its daylight killings set to the Allman Brothers Band’s Midnight Rider. No one in this movie has ever smelled good: everyone is sweaty, in the same clothes the whole time, reeking of sawdust, greasepaint, and cheap bourbon.

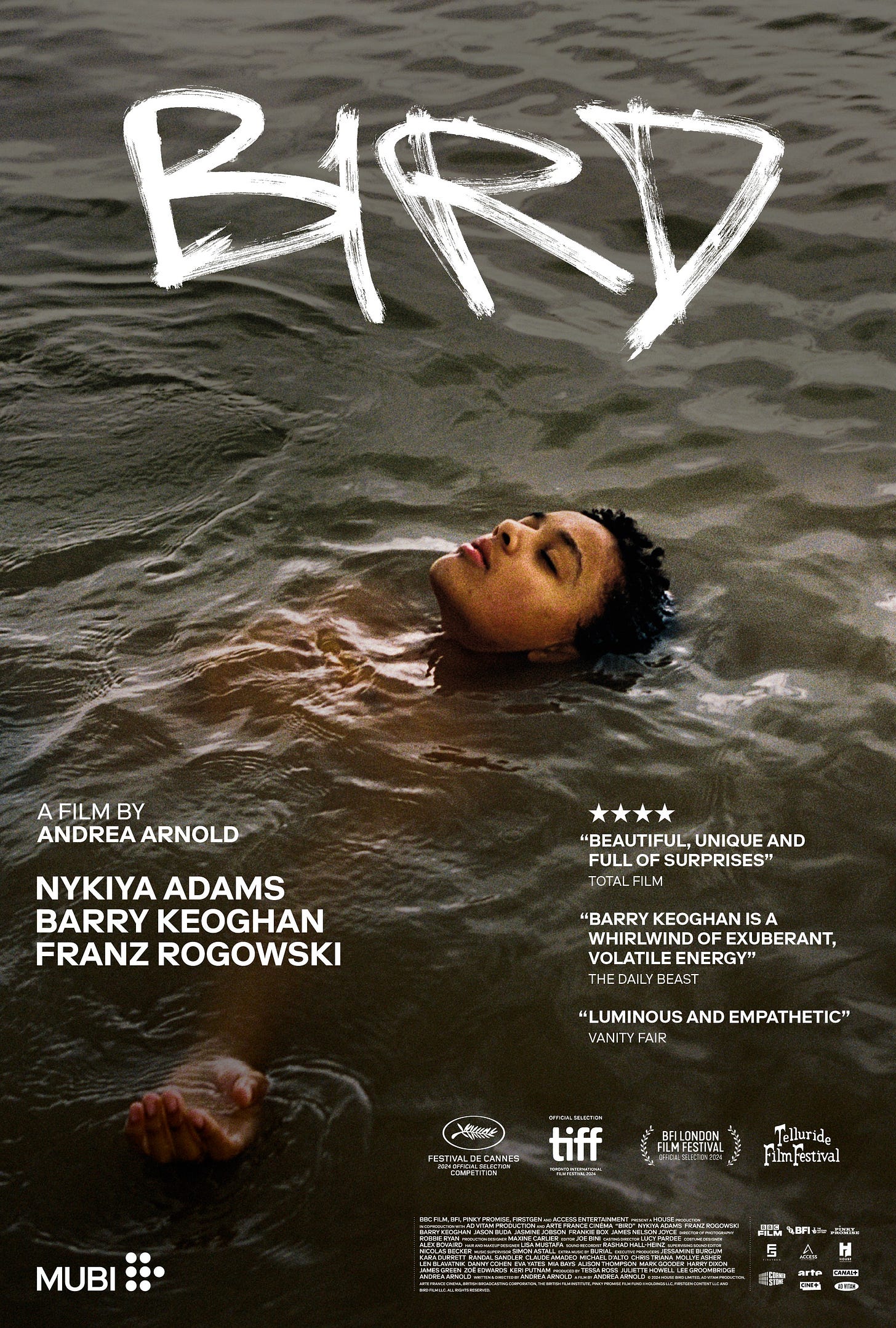

But it is The Fugitive Kind’s idea of birds who sleep on the wind as another metaphor for outsiders that brings me to the third film I’ve watched in 2025: Andrea Arnold’s Bird. Another story of those who don’t belong, who cannot be tamed, who seek escape. As with her previous efforts, American Honey and Fish Tank, Bird’s cast is made up of both professional and non-actors. Bailey (Nykyia Adams) feels somewhere on the same wavelength as Vic in Celine Sciamma’s Bande des Filles/Girlhood—seeking belonging, experimenting with what feels right in terms of gender expression, all the while navigating puberty in tough surroundings. Bailey seems to exist in a world where they rarely bathe, existing in that limbo of not being quite sure whether you need to shower because your body hasn’t begun to really smell every day. Bailey moves through housing estates and fields, passing young men riding horses bareback, clad in board shorts and hoodies. Only with the advent of their first period do we discern Bailey’s age, as they wake to find menstrual blood in their sleeping bag. I remember being puzzled by my first period, around that same age and although I knew what periods were I had no idea what it might really look like when it arrived.

Bailey meets Bird (Franz Rogowski) in a field one morning, and decides to help them find their parents. Bird, as embodied by Rogowski, is fey and gentle, yet entirely self-possessed. Bird is someone who seems to sleep on the wind, coming from nowhere, with an unplaceable accent, dressing in garments that seem chosen but also found, not unlike the way Lee dresses in Guadagnino’s Bones and All. I can imagine Bailey and Bird smell the same, of lived in clothes, of the field or the sea, they smell of where they have been. Like The Devil’s Rejects, this film also has a fascinating soundtrack, comprised of an electronic score by Burial, interleavened with tracks from Sleaford Mods (whose lead singer also has a brief cameo). There is also a cane toad, acquired as a quick cash grab by Bailey’s exuberant young father, Bug (Barry Keoghan, who remains shirtless for pretty much the whole movie, btw and who left Gladiator II and then did this project instead), a toad who will only produce the sought-after hallucinogenic slime if serenaded in complete sincerity with Coldplay’s Yellow. As ever, Arnold is good at showing us community and its outsiders, and how those ties of family can bend or break.