The world of In the Cut smells of garbage and smoke, of sweat and, to borrow a phrase from Jamie Stewart’s Anything That Moves yet again, “worldly jizz” (109). It is filled with “girls that smell like Britney Spears and coconut” (“Mermaids” Florence+the Machine), the mustiness of second hand clothing stores, industrial paint in the halls of public schools and rundown apartment buildings, the glitter and gum of the Baby Doll Lounge dancers, the incense at Pauline’s (Jennifer Jason Leigh) apartment doorway.

The detective, Malloy (Mark Ruffalo), tells Franny (Meg Ryan, unrecognizable in her greatest role) about the murder that has taken place in her neighbourhood. Of the victim he says: “her throat was cut and then she was disarticulated”—Franny writes down ‘disarticulated’ and that’s the word I remember from this film too. To be taken apart, which is of course another word for dismemberment, but disarticulated also evokes silencing, the removal of words, of speech, of vocabulary. I think about my own vocabulary, how I don’t tend to invent words but I like invented words (‘aromatory’), I like slang, and I like French. I like the way some people are starting to say ‘pussy’ like it’s an ordinary word.

I like the sound of high heels on pavement.

I like voice notes.

To be taken apart is also a sex thing, to be undone, is sometimes how people describe that desire. When I was making notes on my phone as I watched In the Cut, ‘throat’ autocorrected to ‘thirst’ making the phrase ‘her thirst was cut and then she was disarticulated’ and I think about this a lot. How Franny says she’s scared of what she wants, that it’s a lot. And I think about the things that I want, how sometimes there is so much more that I want. I think about some of Tracey Emin’s work, how she’s the artist who chose Gustave Courbet’s l’origine du monde for Musee d’Orsay’s Instagram in 2020 during lockdown, how somewhere there is a photograph I was convinced was taken by Emin, of a woman with her legs spread, gathering coins and bills up towards her crotch, and this image has a title that’s about desire or want or something like that but now I wonder if I made this up. I think about Emin’s huge sculpture at Jupiter Artland, I Lay Here For You, and how when I went to see it in July 2022 I described it as ‘a whole pandemic vibe.’

Emin always makes me think hard about being in my body, about the things that happen to women, or when you’re read as femme, and I think that’s part of what keeps me coming back to In the Cut.

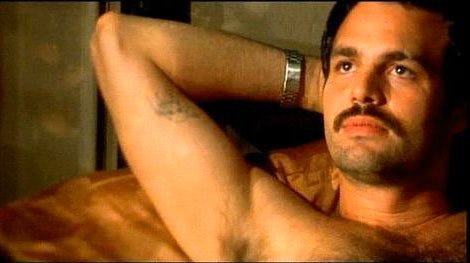

I imagine that Malloy smells good, that he probably cares about that. He comes across as someone who is conscious of how appealing his body is, his torso is a little soft, not too defined, covered in dark body hair (don’t make your actors get waxed unless that’s their thing, please. It’s hot when they have body hair), and his rather devastating manner. I like that when we first meet Franny and Pauline they read like lovers, rather than sisters, that they cultivate that ambiguity in their intimacy. Pauline seems like a woman who has various perfumes, sweet and very floral, maybe something like Concordia by Memoize, which has jasmine and vanilla, as well as pomegranate and fig, where Franny feels like Shadow by Pictor Parfum: tobacco, olibanum, suede, cedarwood. Pauline’s perfume feels super femme while Franny’s is more androgynous. Both these perfumes feel ‘cool’ in some way, evocative of the two women’s darkness, the way they hold back and then let go, the way they do the things they do.

Early in the film, Franny meets her student Cornelius in a bar. On her way to the bathroom she stumbles upon a woman giving a man a blow job. Franny watches them: we see his cock in close-up, the woman’s lips on it, her curved, mermaid blue nails, the tattoo on his inner wrist as he holds her hair, pulls it, and the flare of his cigarette in low, red light. The aromas of this sequence hit you in the face: cum, hairspray, fruit flavoured lipgloss, cigarette smoke, and in the distance some kind of cheap air freshener to disguise the smell of drains in that dank basement.

Later, Franny masturbates imagining Malloy is the man in that basement, and that he is watching her. She looks like Emin’s sculpture, the pose is the same. She cums and immediately gets a cramp in her calf. I think this fantasy is part of the “a lot” that Franny refers to later, because Franny is a feminist but she also wants attention, and she’s not entirely sure how to reconcile this.

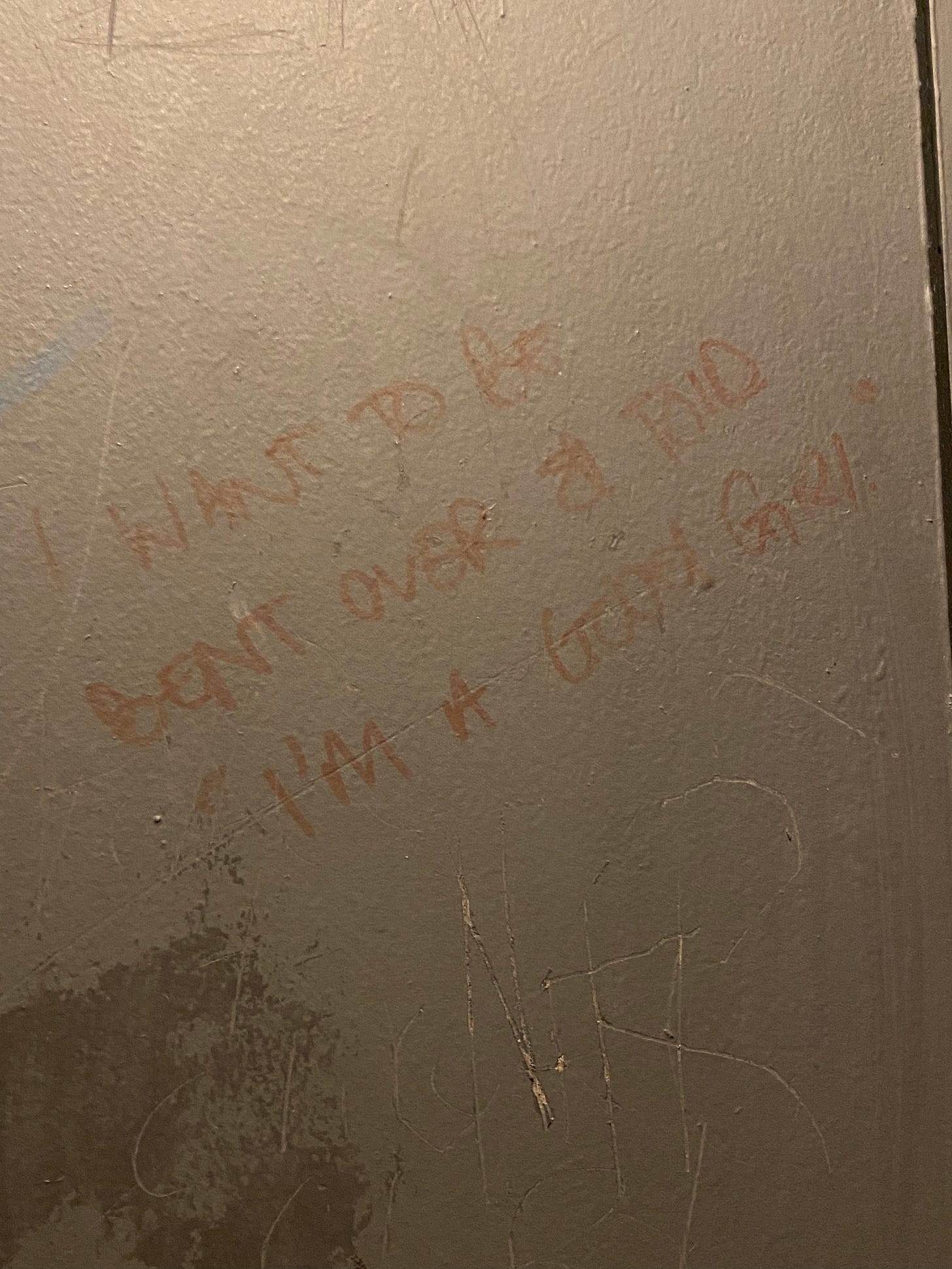

This is a photo I took in the stalls of the women’s bathrooms at SWG in Glasgow. Appropriately, I was there to see Ethel Cain (one of the patron saints of longing and sluttiness). I looked up and there was this graffiti. I think this is something that might resonate with Franny and Pauline, particularly considering this exchange:

Pauline says “you let that detective fuck you”

Franny: “I didn’t let him, I wanted to” Franny has lain there, but not just ‘for’ someone.

Pauline: “you know I remember every guy I ever fucked by how he liked to do it not how I wanted to do it” (And that, friends, is why heterosexuality can be…a challenge.)

However, In the Cut is probably my favourite ‘erotic thriller’ (if we must give it a genre tag) mainly because of this:

“I can be whatever you want me to be”

Malloy says this to Franny and it is honestly so hot I could die and Campion knows this. This is a line that is normally put in the mouths of women, of femmes, and to have him say it shifts the dynamic:

“You want me to be your best friend, and fuck you, treat you good, lick your pussy, no problem”

(Chrissssssttttt. Feel free to go get a glass of water and come back in a bit. If you smoke, now is probably the time.)

He undresses, lies on her bed. She takes off her dress, he takes off her underwear, and she lies down on her stomach while her licks her ass, pussy, and feet. It’s absurdly hot, like the sex Sailor and Lula have in Wild at Heart. The thing about In the Cut is that no one apologises for what they want in bed and no one is ashamed of their body.

But then, there are the murders, the sense of threat and vulnerability that is threaded through the narrative. It is this feeling, of not knowing who you can trust, of thinking that maybe, just maybe, the body doesn’t lie when you know perfectly well that it can, that give In the Cut its sting. “How many ladies have to die to make it good?” Franny says when one of her students complains that To the Lighthouse is boring. The question here is not so much how many ladies have to die to make something good, but how we attach importance to death as a marker of seriousness. It sometimes feels as if we cannot have a film that takes sex and desire seriously, unless it is set up against violence and death. This juxtaposition is the love there is no cure for, as we all sometimes think like Franny’s student, that death is what makes it good.

The photos I refer to are from the early 00s, from a performance Emin did and had documented. One is called I’ve Got It All.

There’s now an uncut version available from Mill Creek entertainment!